Niger's military junta has just hours to restore ousted President Mohamed Bazoum to power or face the possibility of military action from the regional bloc Ecowas.

Last Sunday, West African leaders gave the coup leaders a week to comply with its demands or it would "take all measures… [which] may include the use of force".

But in Niger's neighbour, Nigeria – where the bulk of the troops are likely to come from – voices against the involvement of the military are growing louder.

The two countries also have close ethnic and historical ties.

On Saturday, the Nigeria's senate urged the government to look at "political and diplomatic options".

And in the northern Nigerian city of Sokoto, bordering Niger, which is home to the army's 8 Division, the anxiety is increasing.

It sits on a major junction on the road leading to Niger and is likely to be a mustering point for troops before any military action.

The serenity of Sokoto's residential neighbourhoods belies the heightened tension in the city and the wider north-western state.

One aspect feeding this is that – according to locals – one in every five residents in Sokoto is from Niger or has connections with the country.

Sokoto city's sprawling suburb of Sabon-Gari Girafshi is predominantly inhabited by people from Niger. They fear that military intervention by Ecowas could greatly affect their family members and even jeopardise their own security here in Nigeria.

Image source, Gift Ufuoma/BBCImage caption, Sulaiman Ibrahim has been desperately trying to reach one of his wives who is living in Niger

Image source, Gift Ufuoma/BBCImage caption, Sulaiman Ibrahim has been desperately trying to reach one of his wives who is living in Niger

Fifty-one-year-old jewellery maker Sulaiman Ibrahim lives in one of the fenced and gated compounds.

One of his wives and some of his children are in Niger's capital, Niamey, trapped there because of last month's coup.

"Now I want to call my wife Fatima to hear from her, because since the day of that coup, I have not heard from her," he tells the BBC, gripping his phone in his left hand.

He scrolls through his contacts and dials the wife's number again.

Each call returns with the same message: "The number you are calling is not available at this time."

"Every time I called, this is what they're telling me, either no service or whatever, I don't know," he says in anguish, unable to hide his concern.

"If military action is going to be taken on Niger, this will bring more anxiety. I'm in terrible situation because my family is not with me and I don't have any information about them."

He opens the photo app on his phone to show his 18-year-old son and one of his siblings.

"Here is my son Mustapha, he's currently in Niger. This is his younger brother, he's six years old, they're with their mother."

Sulaiman is not alone.

Daily he meets with other neighbours from Niger to check if anyone has got news from home.

Mohamdu Ousman 43, echoed the sentiments of many here that the use of force to restore the ousted president in Niamey could be catastrophic.

"For Ecowas to go to Niger with the intention to take back power from the military to civilians, we don't wish for that, God forbid. It's like erasing our history," he told the BBC.

Image source, Gift Ufuoma/BBCImage caption, Sabon-Gari Girafshi is home to a large number of people who are either Nigerien or have connections to the country

Image source, Gift Ufuoma/BBCImage caption, Sabon-Gari Girafshi is home to a large number of people who are either Nigerien or have connections to the country

Zainab Saidu, 59, hails from the Nigerien city of Dosso, but has lived most of her life in Sokoto after getting married to a Nigerian man. Her youngest son is currently in Niger and she fears for his safety.

"I'm disturbed, I swear we're in fear all of us, everyone who is from Niger. Everybody is terrified most especially when we heard that Nigeria [might] go to Niger for a war purpose," she says.

On Friday, West African military chiefs said they had agreed a plan for possible military intervention, but Ecowas continues to push for a diplomatic solution.

In an effort to apply other pressure, the regional bloc has also imposed sanctions on the coup leaders and closed the borders into Niger. In addition, Nigeria has cut electricity supplies to its northern neighbour.

But this has meant that those on the Nigerian side of the border are also affected.

Image source, Gift Ufuoma/BBCImage caption, Lorries have been stuck at the Nigeria-Niger border

Image source, Gift Ufuoma/BBCImage caption, Lorries have been stuck at the Nigeria-Niger border

One border town that is feeling the impact is Illela, about 135km (85 miles) from Sokoto city.

It's a commercial hub, but is currently wearing the look of a community under economic stress.

At its entrance, there are long lines of stranded vehicles, mainly large lorries with their loads covered with tarpaulin to shelter them from the rain and the sun.

Gathered in the shade of the lorries are drivers either sleeping or sitting with their phones or radios, waiting for news of the latest developments about the border.

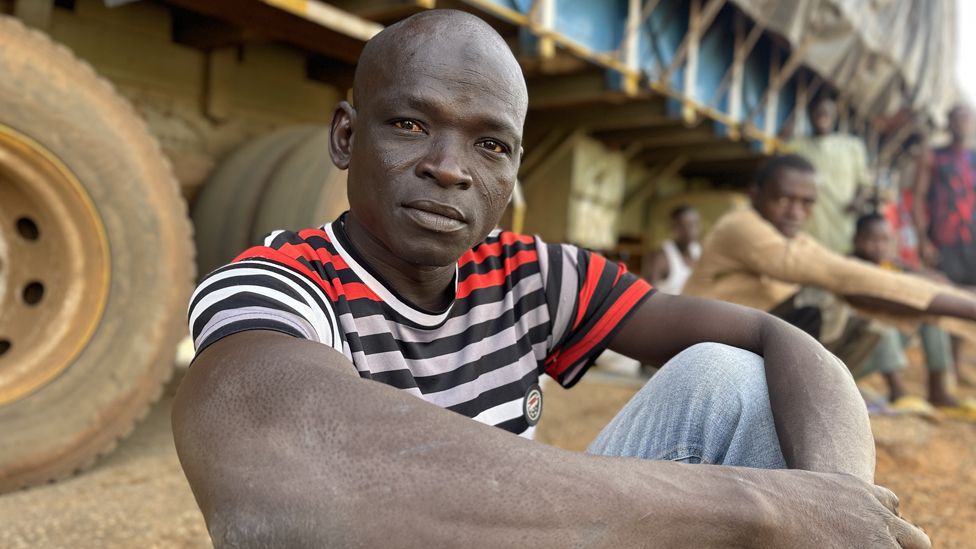

Image source, Gift Ufuoma/BBCImage caption, Driver Abdullahi is running out of money

Image source, Gift Ufuoma/BBCImage caption, Driver Abdullahi is running out of money

One of the drivers, Abdullahi, dressed in a T-shirt and faded blue jeans, is holding a sachet of water.

"I have been stranded here for the past three days," he says.

"I have exhausted myself financially. Now I don't have any money. A friend bought food for me this morning. That's why you see me holding the water. I have been calling my boss to explain my plight and to let me know that the border closure has affected me, but he's not responding to my calls."

His colleagues also look tired and resigned.

They could face a long wait and the goods that they are carrying could perish, costing the business owners huge sums of money.

Others whose businesses have been seriously hit include Ado Garba Dankwaseri.

Image source, Gift Ufuoma/BBCImage caption, Ado Garba Dankwaseri is now not able to supply others in the town with ice after the border closed

Image source, Gift Ufuoma/BBCImage caption, Ado Garba Dankwaseri is now not able to supply others in the town with ice after the border closed

The 42-year-old often travels into Niger to buy ice blocks to supply to traders in Illela selling water and soft drinks who need to keep things cool.

But Ado Garba's business has been hit hard and he is unable to make the trips to Niger for his supplies.

"I make 100,000 naira ($130; £100) a day with my supplies. But right now, I cannot cross the border. There are soldiers, police and custom and immigration officers stationed everywhere. You cross the border at your own peril," the ice trader says.

Customs officials met some of the business people in Illela on Friday to try to address their concerns and talk about why the closure was necessary.

"There's no sacrifice too big as long as they are able to achieve peace and democracy within the sub-region. The community understands the reason behind the border closure," says Bashir Adewale Adeniyi from the customs service.

But the patience of people in Illela and elsewhere in Sokoto is being tested – and so far, there has been little obvious sign that Niger's coup leaders are willing to back down.

![]()